Salt & Light

The following is the text from the Sermon I preached at The Episcopal Student Center at Texas A&M for Epiphany 5, Year A.

You can find the Gospel story that this Sermon is based on here: Matthew 5:13-20

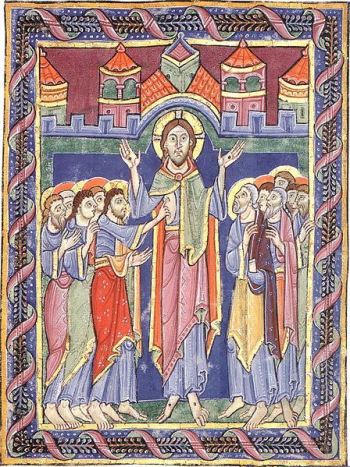

Tonight’s Gospel story drops us smack-dab-in-the-middle of what we typically call “The Sermon on the Mount.” Jesus has been surrounded (again) by a hoard of people wanting to hear him teach or be healed by him or see him do something miraculous, so he hikes up a mountain and his disciples follow him up there. His sermon with them begins with the beatitudes, you remember these:

These are all the “blesseds”…”Blessed are the poor in spirit, those who mourn, the meek, those who hunger and thirst for righteousness,” etc. We will save those for another Wednesday night..

But right after he has described all of these ideal characteristics of the life of his followers and what benefits that lifestyle will bring, we get tonight’s section about being salt and light. So if this passage is going to be anything more than “a nice Jesus saying” for us, we need to dig a little deeper into this text.

What do we know about salt then and now?

– Commodity, precious, used in the meal that sealed a covenant

– brings flavor to something bland – makes a food “come alive”

– used to enhance the tastes of food

– used as a preservative, keeping something that might otherwise go bad

– used to stimulate thirst

What do we know about light then and now?

– no electricity, so sun and fire were only sources of light

– enables us to see things we couldn’t see otherwise

– a kind of energy, solar power

– gives color

– helps vegetation to grow

– can be focused for specific uses – like a giant laser

So, in his sermon, Jesus is specifically calling his disciples, those who follow him, salt and light. In the biblical language we may lose some of the power of this calling, so listen to a more modern paraphrase adapted from author and Episcopalian, Lauren Winner:

YOU, beloved, are the salt of the earth. But if salt becomes stale and loses its saltiness, can anything make it salty again? No. It’s useless.

It just lies there, white and bland and grainy…

And YOU, beloved, are the light of the world. You can’t hide a city built on the top of a hill – at night, it’s lit up and stands out so much that you can’t miss it.

It would be silly to light a lamp and then stick it under a bowl. Either the light would go out or it would catch the bowl on fire and the whole purpose of lighting the lamp in the first place would be lost. When someone lights a lamp, she puts it on a table or a desk or a chair, and the light illuminates the entire house. YOU are like that illuminating light. Let your light shine everywhere you go, that you may illumine creation, so men and women everywhere, even in the church, may see your good actions, may see creation at its fullest, may see your devotion to me, and in response to your light, may turn and praise your Father in heaven because of it.[1]

Cool paraphrase, huh?

At the time when Jesus is preaching this sermon up on the mount, the Jewish people are in the midst of great theological and social tension. Remember that Israel is occupied by the Roman Empire — so you could say that this people who had lived in some form of exile or another for almost 600 years at this point, are now living in a kind of exile in their own land. The peace is being relatively kept, but Roman Rule is the heavy-handed law of the land. And, understandably, the whole Jewish community is in huge conflict over the future of Judaism and what it meant to be Jewish under these circumstances. And they are asking lots of hard questions that they don’t have any answers for: How can it be that the Holy City of God is now occupied by pagans? What does this say bout God’s relationship to us? What does God want us to do? How are we to respond? What will our lives, our faith look like in the next 50 years?

Each of the different groups of Jews sought out answers in very different ways, ranging from the Sadducees — who were forming collaborations and questionable alliances with the Roman occupiers, to the Zealots — who wanted to form a militia and stockpile weapons so they could overthrow the Romans. Then, there were the Pharisees – some of whom wanted to take up the sword, but most of whom,

“opted for [forming a kind of] ghetto; realizing that the small Jewish nation was no match for the vast military resources of the empire….[so they instead turned inward, going] deeper into private study and practice of Torah.

If [they] could not obtain [their] political independence, at least [they] could preserve [their own] cultural and religious identity.” [2]

So, at the time that Jesus preaches this sermon on the mountain, the whole community of Israel is (and has been for centuries) deeply afraid that they are going to lose themselves.

You and I are living during a time of major shift and change in our church.

“Many [of the] values and practices from [our parents, grandparents and great grandparents’ generations] are being questioned and jettisoned. [Denominations like ours] are getting smaller, and losing social [standing].”[3]

As a result, many of our well-intentioned elders in the church, are doing their best to be as faithful as they can be AND are yet, are living in a place of fear right now.

They are asking the same questions of our faith community that the Jews in Jesus’ day were asking:

Given all the craziness and change in the world around us -what does it mean to be a Christian, to be an Episcopalian these days?

Who do we have to hand our traditions and our beliefs down to?

What will our faith look like in the next 50 years?

This church we know and love seems to be changing, no matter what we do to keep it the same – what if it changes so much that we don’t recognize it anymore?

From that place of understandable fear and uncertainty, in the midst of asking those hard questions and not yet knowing any of the answers, I’m afraid the leaders of our churches often turn inward and start clinging desperately to anything and everything they can that, in their minds, resembles “how things used to be.” They resist change, sometimes at all costs and the church risks becoming a ghetto of pious and very faithful older people that is less and less meaningful to the world outside.

They do it because they are afraid.

They do it because they understand it as the most faithful thing they can do.

They do it because some of the things that they have believed their whole lives about the bible and about Jesus and about being a community of faith are now being questioned in the church.

They do it because they want to maintain our identity as Episcopalians and because they want protect the faith that our church has inherited from centuries of Anglicans before us.

They do it because the future of the church is quite unsure and probably doesn’t look as much like the past as they’d like.

And, my beloved college students, they do it because they don’t know you.

They don’t know you.

They don’t know about the amazing gifts that you bring to the table. They don’t know how deeply you love Jesus and how committed you are to following him. They don’t know your passion for becoming a community that loves each other well and makes a difference in this world. They don’t know that you love MANY things about our Episcopal identity. They don’t know that you may be frightened about some of the same things they are. They don’t know that you really want to be here, to be part of the church, to be leaders in the church. They don’t know you.

And how can they trust what they don’t know?

How can they entrust this church that they have loved and that has loved them to people they don’t really know?

And because they are afraid, YOU are going to have to be the ones that make the effort.

YOU are going to have to do the work of letting them know you. It’s not fair. But there it is.

And this is why I don’t water down the scriptures with you in sermons or in bible studies.

This is why I hold you all to a really high standard, and call you out when you aren’t living up to it.

This is why we are building as inclusive a community as possible.

This is why we are grooming a Vestry and training Sacristans.

This is why every week we practice the fullest liturgy of the church that we can – with Candlemasses and Lessons and Carols and Feast Days and worship services that sometimes take longer than you’d like.

Because in the midst of a church that is afraid it’s going to lose itself, Jesus is up on the top of a mountain preaching tonight to this congregation, saying:

YOU are the salt our dish needs.

YOU are the light our shadows are longing for.

Become the kind of followers who draw out the bold flavors that are sometimes hidden in our churches. Enhance the way we taste to the rest of the world so that we aren’t too bland. Preserve those ancient practices that are meaningful and sacred rather than letting them spoil.

Become the kind of followers who shine your bright light into the dark corners of our old buildings. Expose the unseen cobwebs that hang from our pews and the dust that covers the ageless wisdom of our prayer books, so that we realize we need to clean some things out and tidy some things up.

Be light in the very places that are crusty and grumpy and distrustful because your light is a source of energy that can give new life to even the most withered plants in our garden.

No more excuses that you are too bland.

No more hiding yourself under a bowl.

The time is coming and is now here for you to step out and become the followers Jesus is pleading with you to be – the very spice and the very illumination that can call a new church into being.